![]() The Mets’ announcement on Old Timer’s Day that they’d retire Willie Mays‘ No. 24 addressed another long-neglected historical oversight of the Wilpon Era. That there was an Old Timer’s Day at all erased a bit of Fred-dom as well.

The Mets’ announcement on Old Timer’s Day that they’d retire Willie Mays‘ No. 24 addressed another long-neglected historical oversight of the Wilpon Era. That there was an Old Timer’s Day at all erased a bit of Fred-dom as well.

Both were solid hits with the fanbase, though the Mets as a brand might have gone a step further had they retired 24 for Joan Payson–or Willie AND Joan Payson–as I don’t believe any club has retired a number for a woman before.

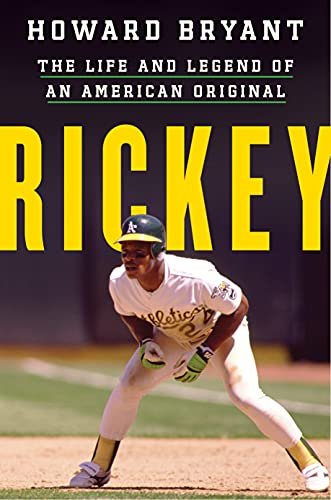

For me personally, it was fortuitous timing as I’d just finished reading RICKEY: THE LIFE AND LEGEND OF AN AMERICAN ORIGINAL, a bio written by ESPN’s Howard Bryant. I read a fair amount of baseball books and I thought this one was outstanding as Bryant writes powerfully about an enigmatic subject he argued was often misunderstood, mocked and degraded even as destroyed one all-time baseball record after another and forced his way into the innermost circle of baseball’s greatest all-time players, including Willie Mays.

![]() When Henderson became a Met at age 40 in 1999, he was issued No. 24 for the first time since it belonged to Kelvin Torve and, it was emphasized at the time, with the blessing of Mays. What Bryant’s book revealed was that Mays was the reason Henderson had the odd distinction of batting righthanded and throwing lefthanded: Though a natural lefty, he simply imitated how Mays hit, and Mays was the reason Henderson was best-associated with the No. 24. Bryant also reveals that Rickey actually preferred No. 35 as “his” number–over his 25-year career with nine different teams, including four separate stints with Oakland–he’d worn 35 in Oakland, Seattle and Red Sox.

When Henderson became a Met at age 40 in 1999, he was issued No. 24 for the first time since it belonged to Kelvin Torve and, it was emphasized at the time, with the blessing of Mays. What Bryant’s book revealed was that Mays was the reason Henderson had the odd distinction of batting righthanded and throwing lefthanded: Though a natural lefty, he simply imitated how Mays hit, and Mays was the reason Henderson was best-associated with the No. 24. Bryant also reveals that Rickey actually preferred No. 35 as “his” number–over his 25-year career with nine different teams, including four separate stints with Oakland–he’d worn 35 in Oakland, Seattle and Red Sox.

When the Mets acquired Henderson as a free agent over the 1998-99 offseason, 35 belonged to Rick Reed.

Henderson was born Rickey Nelson Henley in an Oldsmobile in Chicago on Christmas Day of 1958. His father John Henley soon separated from Rickey’s mother Bobbie who relocated to her hometown in Arkansas then moved with the Great Migration of Southern Blacks to Oakland–a destination of thousands of Black families that became the cradle of dozens of accomplished professional athletes with whom Henderson played with as children in the 1960s and 1970s (Mike Norris, Shooty Babitt, Lloyd Moseby, Gary Pettis, Glenn Burke, Dave Stewart and many others). Rickey took the last name Henderson after Bobbie remarried, and grew up determined to play football for the Oakland Raiders but was persuaded by Bobbie and a local scout, Jim Guinn, that baseball was the safer path. Because of his great ability in sports, Rickey was indifferently educated and hadn’t learned to read by the time he first turned pro.

Henderson was born Rickey Nelson Henley in an Oldsmobile in Chicago on Christmas Day of 1958. His father John Henley soon separated from Rickey’s mother Bobbie who relocated to her hometown in Arkansas then moved with the Great Migration of Southern Blacks to Oakland–a destination of thousands of Black families that became the cradle of dozens of accomplished professional athletes with whom Henderson played with as children in the 1960s and 1970s (Mike Norris, Shooty Babitt, Lloyd Moseby, Gary Pettis, Glenn Burke, Dave Stewart and many others). Rickey took the last name Henderson after Bobbie remarried, and grew up determined to play football for the Oakland Raiders but was persuaded by Bobbie and a local scout, Jim Guinn, that baseball was the safer path. Because of his great ability in sports, Rickey was indifferently educated and hadn’t learned to read by the time he first turned pro.

Rickey is quoted, but sparingly—he’d never been trustful or particularly open with writers—but the book seems driven by input from Rickey’s wife, Pamela, who’d been his sweetheart since she was 14. Dozens of players, managers, writers and fans are interviewed, including Sandy Alderson, Rickey’s GM for much of Rickey’s stay career in Oakland and today is the Mets’ president who summed up how baseball viewed Rickey while predictably using the word “optics.”

In Alderson’s view, even the most astute baseball men … seemed preoccupied with the Rickey optics—the delivery, the flash, the personality, the whispers, the moods. Their inability to see through all that thus diminished his obvious ability in their eyes, partly because of their own prejudices, and partly because Rickey made the optics impossible to ignore. Rickey was a great player but, because of his moods and temperament, he was not quite a leading man. When it came to Rickey, baseball men focused on what he wasn’t often more than on what he was.

Although admired by fans for peculiarities that became urban legend (including the facetious John Olerud story, addressed within) Rickey was not a “class clown who reveled in what he did not know,” Bryant asserts. “He was a ferociously competitive, goal-driven athlete.” He never remembered names because that was difficult for him but his determination was such that he never forgot a perceived slight, whether it was money and respect (salary arbitration players who made more money than him, like Jose Canseco, or endorsement deals) or in competition with pitchers or catchers who prevented him from stealing bases) or writers (“The press wanted it have it both ways with Rickey: they wanted him to cultivate and trust them while they simultaneously mocked him,” Bryant writes).

Rickey became as Met only months before this site was launched. At the time my enduring impression of Rickey was that shared by many white guys who’d seen his career form afar: He was a buffoon who diminished his own stolen-base record by declaring he was “the greatest” on the same day Nolan Ryan pitched his seventh no-hitter and reacted with “class.” On that day, May 1, 1991, I was putting together the sports page for a small daily newspaper and had my own aspirations to one day be a big leaguer in that field. I was certain then I was right and would have said then race hadn’t a thing to do with it. I was wrong about that, and Bryant’s book reminded me so. So did a resplendent season in 1999, perhaps Rickey’s best late-career year.

Here’s something else I’d forgotten about Rickey, he was a Mets’ coach in 2007.

Go buy Howard Bryant’s book.

Viewing the new regime’s agenda as (in part) canceling debts with the fanbase as interesting. I looked at the agenda of the early Doubleday/Wilpon era the same way, as they reacquired first Staub, then Kingman, and finally Seaver.

They did everything right at the beginning including great trades and upgrading the mediocre, post-Nelson TV announcing.

Now you can’t help but notice the new director for the broadcasts is doing things never done before. Angles, effects, letterboxing etc